[ad_1]

Reduce, Reuse and Rethink is a CBC News series about recycling. We’re exploring why our communities are at a turning point and how we can recycle better. You can be part of the conversation by joining our Facebook group.

Since 1992, China has imported 45 per cent of the world’s plastic waste. But at the start of this year, the country shut the door on much of that plastic, leaving countries scrambling to fend for themselves.

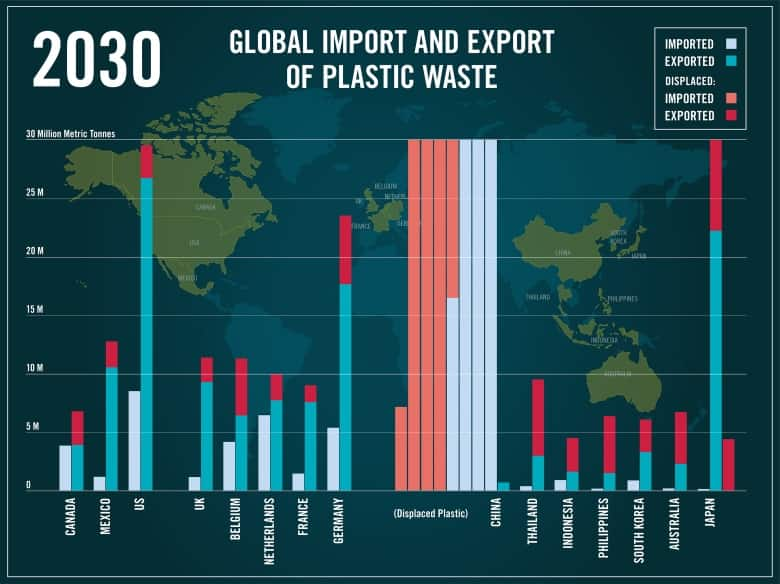

Now a new study suggests there are deep repercussions to China’s new policy: By the year 2030, an estimated 111 million tonnes of plastic waste will be “displaced” and have nowhere to go.

“We’ve seen reports of plastic waste and other types of waste that are impacted by the ban accumulating within these countries that have long been dependent on China,” said Amy Brooks, lead author of the paper, published in Science Advances, and a PhD student at the University of Georgia.

“Now it means that waste can be landfilled, which is not good. It could be incinerated, or could potentially be sent off to other countries in the region that also don’t necessarily have the waste management infrastructure.”

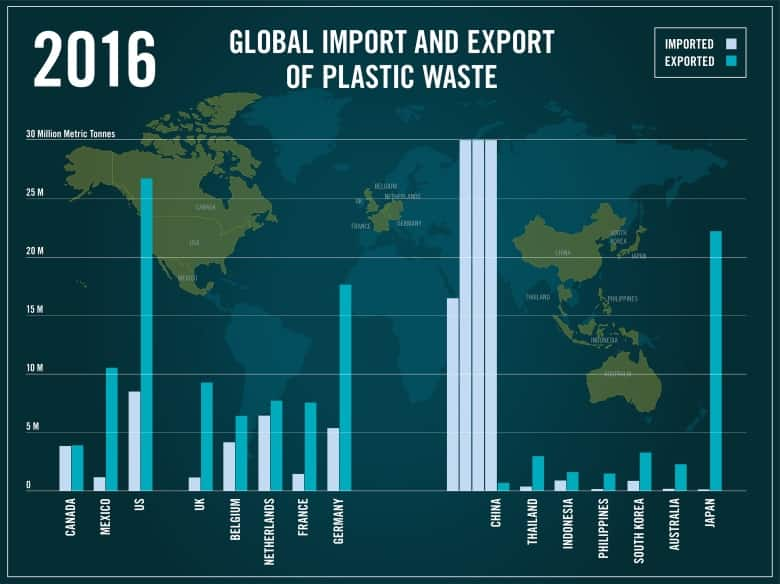

This graph illustrates the cumulative trade of plastic waste in 2016. (Lindsay Robinson, University of Georgia)

The United Kingdom has already begun diverting its plastic waste to nations such as Malaysia and Vietnam, countries that have less effective waste management infrastructure.

Brooks notes that some of these nearby countries are now talking about implementing a ban similar to China’s, which refuses to take anything with a contamination of 0.5 per cent.

“It’s having a kind of domino effect,” she said.

The ban is also highlighting a growing need for countries to look for solutions at home.

“Frankly countries like [the U.S.] and Canada — these high-income countries, wealthy countries that have waste management infrastructure — need to move toward domestic management,” said Brooks.

We all got hooked on a drug called ‘China.’– Joe Hruska , Canadian Plastics Industry Association

Canada is in a position to do just that, even if we are faring better than most countries when it comes to exporting plastic waste, said Joe Hruska, vice-president of sustainability for the Canadian Plastics Industry Association.

Countries — including Canada — turned to China early on when it came to recycling, he said.

“We all got hooked on a drug called ‘China,'” he said.

But Hruska said the time has come to look inward to improve what he says is already a successful plastics management system.

Many Canadian provinces have an extended producer responsibility policy — or EPR — in place, he said, which makes the producer responsible for a portion of the financial costs of a product’s life cycle. But such policies have not been adopted universally.

“I see it as a huge opportunity for Canada to actually push the plastics circular economy to higher levels,” Hruska said.

Wake-up call

Looking at the data collected by the researchers, China’s decision should perhaps not be so unexpected.

High-income countries have been the primary exporters of plastic waste to China since 1988, the study notes. Canada was the 10th top exporter.

And China has its own mountain of plastic waste to deal with, coupled with limited infrastructure.

The researchers estimated that between 1.3 to 3.5 million tonnes of plastic enters the oceans each year from China.

A worker separates plastic bottles at a recycling depot in Beijing in this May 2013 file photo. According to government figures reported in local media, about 4.67 million tons of recyclable waste was collected in Beijing in 2010. (Kim Kyung-Hoon/Reuters)

And based on data from 2010 to 2016, the imports to China add a further 10 to 13 per cent of mass to the plastic waste the country itself is generating. It’s something the researchers believe is unsustainable.

For Brooks, one of the most surprising findings was that 90 per cent of the plastic waste China had accepted was in the form of one-use plastics: specifically water bottles and food wrap.

“So that is an easy target, to me, where we can reduce plastic use,” Brooks said.

With China’s ban in place, the researchers conclude much of the plastic waste being diverted may end up in landfills.

But the onus shouldn’t just be on industry: An oft-touted refrain from both the plastics industry and environmentalists is that the issue isn’t an easy fix — and it needs to be done on several tiers.

This illustration projects displaced plastic waste by 2030. (Lindsay Robinson, University of Georgia)

“It really requires a lot of collaboration between government, industry, the consumer [and] municipal governments,” said Hruska. “I think, if anything, we need to be leaders and have leaders who have a vision. And I don’t think that vision has been solidly established.”

In the meantime, countries around the world are left scrambling to find ways to deal with their own plastic waste.

“Hopefully it’s a wake-up call,” said Brooks. “We need to make global change; we need to make local change.”

[ad_2]