[ad_1]

A feast was held at Sun Valley School on Monday as the culmination of a project on reconciliation and to offer thanks to a residential school survivor who came to speak to the students about his experience.

“He came out and told stories about his journey throughout childhood into adulthood and really touched upon residential schools,” said Robin Paul-Ballard, Grade 5 teacher at Sun Valley.

“Which was really eye opening for the students.”

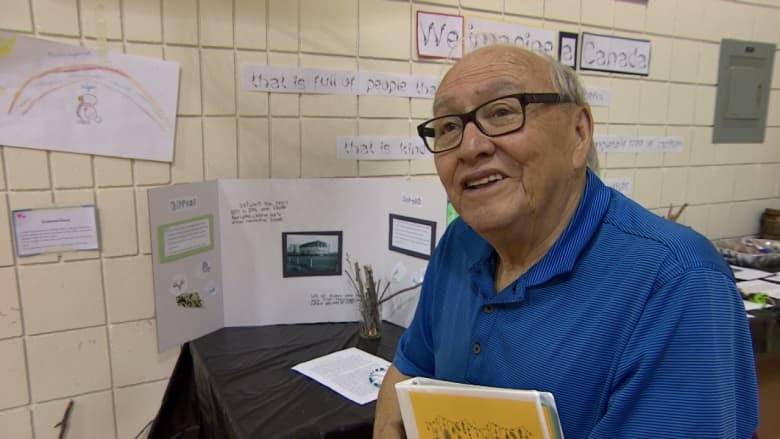

Theodore Fontaine, a member of the Sagkeeng First Nation, spent nearly 12 years in two residential schools growing up.

The 76-year-old visited the Grades 4 and 5 students at the French immersion school in May as part of a unit on reconciliation and Canada’s history with Indigenous people.

Over the last couple weeks, the students put together their own personal projects to reflect what they had learned.

Grade 5 French teacher, Robin Paul-Ballard, said students “soaked up every piece of information” about residential schools after hearing stories from survivor, Theodore Fontaine. (Holly Caruk/CBC)

“They did projects from making dream catchers, to doing research on famous aboriginal people like Tommy Prince, or making timelines,” said Paul-Ballard.

“I wanted it to be their own reflections and their own reconciliation process.”

The school held the feast to celebrate and showcase the students’ work.

They enjoyed entertainment from a Métis fiddler and guitarist, a hand-drummer, and paid thanks to Fontine with a book of their thoughts on what they imagine Canada could be.

“Responses such as, I imagine a Canada that is respectful, I imagine a Canada without racism, I imagine a Canada where we are kind to one another,” said Paul-Ballard.

Helping kids relate

Paul-Ballard said Fontaine’s visit sparked numerous questions and conversations in the classroom.

“They listened and soaked up every piece of information that he was giving and they wanted more, you could see it, they loved his stories,” she said.

Paul-Ballard said the topic isn’t easy to discuss among students aged nine to 11, but said it’s important to start the conversation that will continue throughout their education.

“We wanted to present it in a way that doesn’t cover anything up, we talk a lot about truth and how sometimes learning the truth isn’t necessarily a really joyous experience,” said Paul-Ballard.

“That there is a truth to Canadian history that we need to learn in order to change and grow from, but it will be painful,” she said.

Theodore Fontaine from the Sagkeeng First Nation was taken to residential school when he was seven years old. He spent time in Fort Alexander and Assiniboia Indian Residential Schools from 1948 to 1960. (Holly Caruk/CBC)

“The loneliness that we had, the hunger, not being able to see your family for months at a time,” said Fontaine.

‘I couldn’t even imagine going to a school like that’

Lian Hanzmann, 10, did his project on Sgt. Tommy Prince, one of Canada’s most decorated First Nations soldiers.

“He went to a residential school and then when he died he wasn’t like honoured or anything, he was out on the streets with nowhere to go or no one to turn to to help.”

“It makes me feel super mad, cause just ’cause he’s Aboriginal doesn’t mean that he can’t be honoured like someone else, everybody should be treated the same,” said Hanzmann.

Hanzmann said while he was excited to learn about history, he was also saddened by Fontaine’s stories.

Lian Hanzmann, 10, did his project on Sgt. Tommy Prince, because he loves history and learning about war heroes. (Holly Caruk/CBC)

Katherine Durand, 11, did a timeline of residential schools to document how long they were operational.

“Lots of the residential schools were open for a really long time,” she said.

“They were really bad, they shouldn’t have been there. I don’t think that people should have lost their culture.”

Durand said she enjoyed listening to Fontaine speak, and his stories inspired her research.

Katherine Durand, 11, made a timeline of residential schools operations. (Holly Caruk/CBC)

‘I grew up with shame’

Fontaine said despite his extensive work with youth, he still has a hard time talking about his experience.

“I’m not comfortable yet, but you get to the point of being able to reconcile and say ‘it did happen,'” said Fontaine.

“As a seven-year-old, I lost who I was, my culture, my language, it was knocked out of me. And when I grew up, I grew up with shame and a reluctance to be able to confront it,” he said.

“A lot of our people are still unable to reconcile to the fact that they’re Indian, because it was such a negative connotation.”

Fontaine said he felt privileged to be a part of the students’ learning and praised teachers for including reconciliation in their curriculums.

“They’re developing such wonderful leaders of our country,” said Fontaine.

[ad_2]