[ad_1]

Image copyright

Image copyright

Getty Images

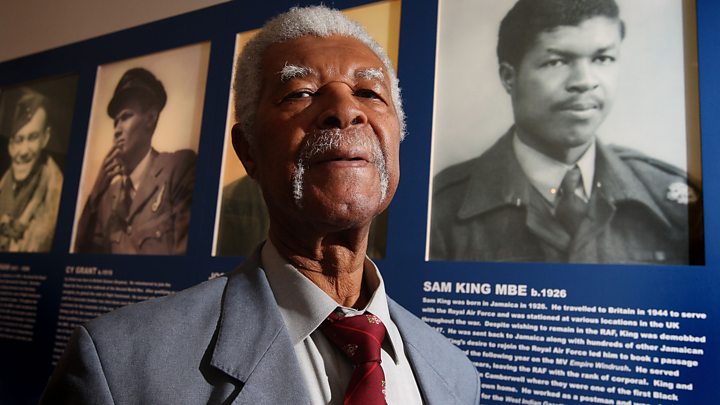

On 22 June 1948, Caribbean immigrants arrived in Essex on MV Empire Windrush to help rebuild post-war Britain

Hundreds of workers aboard MV Empire Windrush arrived in Britain exactly 70 years ago, an anniversary that has an added significance following a scandal that culminated in the resignation of a home secretary.

When it began to emerge what had happened to the children of these Commonwealth citizens – being threatened with deportation despite living and working in the UK for decades – BBC Radio London presenter Eddie Nestor was faced with a difficult decision.

At the time the scandal broke, Nestor – himself a child of immigrants from the Caribbean – had been told he was to be made a Member of the British Empire.

Ultimately, he chose to accept the honour, believing it would help him raise more money for charity and validate his efforts “to encourage everyone, particularly people from a black, Asian and minority ethnic background, to be all they can be”.

But what have other black and ethnic minority people done when facing the same dilemma?

Eddie Nestor is a charity campaigner and the presenter of Drivetime on BBC Radio London

For poet, writer and musician Benjamin Zephaniah, the answer to the question of whether he should accept an honour from the Queen was and remains an emphatic “no”.

Zephaniah, who grew up in Birmingham and is of Caribbean heritage, famously rejected his OBE in 2003 and says he feels “more determined” than ever about that decision in light of the scandal.

Benjamin Zephaniah left school unable to read and write but went on to become one of Britain’s most celebrated post-war literary figures

Having been “writing against slavery, against Empire, against colonialism and against people controlling and ruling over other people all my life, how could I then put Empire, put slavery on the end of it?”, he asks.

“How could I do that and look my people in the face?”

His view is echoed by hip hop artist and dancer Jonzi D, whose parents hailed from the former British colony of Grenada. He turned down an MBE in 2011.

Image copyright

Sadler’s Wells

Jonzi D has been involved in British hip hop culture since the early 1980s

“The British Empire is nothing to be proud of as far as I’m concerned,” he says.

“It’s been the result of murders and annihilations of whole communities all around the world for hundreds of years, so to have this badge that says I am part of the British Empire I think is an offence to all of the victims of the British Empire that are part of my ancestry.”

However, others believe a Queen’s honour can help them to achieve meaningful things.

Activist and author Dr Yvonne Thompson CBE, who moved to Britain from Guyana with her family when she was four, says that although the word “empire” made her “think”, there is no point in “living in the past”.

Instead, she says she chose to move on and try to make the system “better from within”.

Image copyright

Yvonne Thompson

Yvonne Thompson was awarded a CBE in 2003 in recognition of her work with black and ethnic minority businesspeople

Six years ago, she was accepted on to the economy honours committee, which reviews nominations, and she believes her CBE helped her secure the role.

She has made it her mission to increase the number of female and minority ethnic nominations and says: “I think I’ve made a difference.”

Ten percent of those on the most recent honours list were from ethnic minorities – something that was not the case when she arrived, she says.

This sentiment is shared by activist Patrick Vernon, whose parents migrated to the UK from Jamaica in the 1950s.

He believes his OBE has lent greater credibility to a petition he created calling on the government to grant an amnesty to anyone who arrived in the UK as a minor between 1948 and 1971, and thus helped to secure almost 180,000 signatures.

Having a Queen’s honour, Thompson believes, can open doors, although Zepheniah argues that “if that’s what it takes to open a door then it’s the wrong door you’re going through”.

But such an honour isn’t just for the person awarded it but also for his or her family, British soul master Jazzie B says.

Image copyright

BBC/Wall To Wall

Jazzie B was born in London in 1963

The founding father of British group Soul II Soul, whose parents are from Antigua and Barbuda, says he did feel a bit of a “sell-out” upon accepting his OBE in 2008.

But he told the Telegraph that it signified “how far our family had come”.

The musician also felt the award signified vindication against those members of the “establishment” who “kept harassing” him in the past, and helps him “lubricate the situation” when he is “dealing with the authorities”.

Family reasons were also central to Yasmin Alibhai-Brown’s decision to accept her MBE in 2001.

Alibhai-Brown, who was born in Uganda to Asian parents, says she begrudgingly took the honour to please her mother, who had been afraid the family would get deported because of her daughter’s “big mouth”.

But the outspoken newspaper columnist decided to return the award two years later, partly in protest against the Iraq War and partly because she believes the honours system is “corrupt”.

Plus, the word empire “gets under” her skin, she says, and remaining an MBE would have meant accepting that “black and Asian people are still colonised in the mind”.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown was appointed MBE for services to journalism in 2001

It’s not just descendents of those from former British colonies who take issue with the word empire.

Former chancellor of the exchequer Alistair Darling told the Public Administration Select Committee in 2012: “We do not have [an empire]. We are making someone a Commander of the British Empire and we are in no position to offer him such a command.”

Giving evidence to the same committee, George Reid, the Lord Lieutenant of Clackmannanshire, argued that the word empire was “inappropriate to a post-imperial UK”, and said its use often posed problems for British businessmen abroad: “You go round the world and somebody says: ‘So and so is a CBE. What does that stand for?’

“The moment you say the word empire, you wish you did not have to. At one end you get the opium wars; at another you get some battle for independence. All over it smacks of arrogance.”

For royal commentator Richard Fitzwilliams the word empire is “synonymous with imperialism, exploitation and slavery” to many people.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

He argues that the honour titles should be changed from “British Empire” to “British Excellence”, which would allow the abbreviations to remain unchanged.

“There’s never been a specific reason given as to why it’s remained the same,” he says.

A Cabinet Office spokesperson said: “Our honours system plays an important role in recognising people from all backgrounds who have contributed to public life.

“The diversity of the honours system has improved greatly in recent years, with 10% of honours in the recent Queen’s Birthday Honours list received by people from an ethnic minority background.

“Nearly all honours are accepted, and a variety of reasons are given when they are not.”

Listen back to BBC Radio London’s documentary ‘My MBE and Me’ on the BBC iPlayer.

[ad_2]