[ad_1]

The U.S. is the focus of international outrage for its policy of separating children from their parents and detaining them after they cross the border in search of asylum.

But Canada also detains migrant children — and in some cases, restricts access to their asylum-seeking parents — despite the fact its stated policy is to do whatever possible to avoid it.

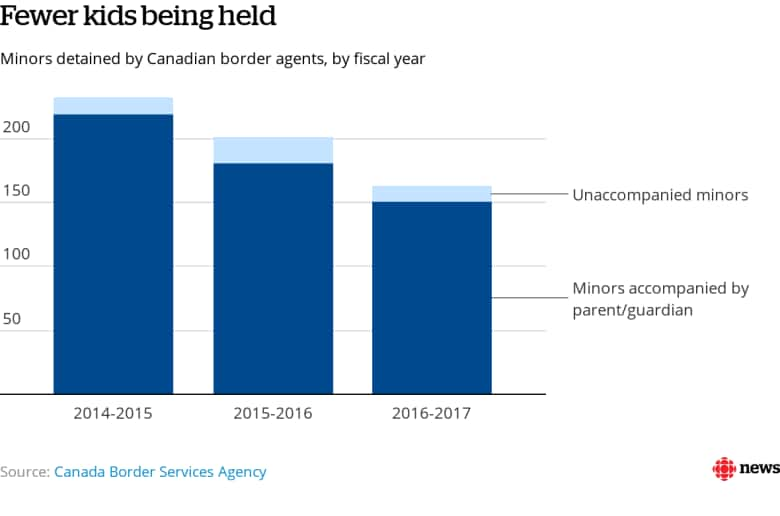

Last year, 151 minors were detained with their parents in Canadian immigration holding centres.

Eleven others were held in custody unaccompanied by an adult, according to the Canada Border Services Agency.

CBSA holds people who are considered a flight risk or a danger to the public, and those whose identity cannot be confirmed.

‘Frightening experience’

The holding centres, which are off limits to the public, resemble medium-security prisons. They are surrounded by razor-wire fences and surveilled by guards.

There are three such facilities across Canada, in Vancouver, Toronto, and Laval, Que. In some provinces, asylum seekers are detained in prisons.

A recent McGill University study found that detention can be a “frightening experience” for children, leaving them with “psychiatric and academic difficulties long after detention.”

Inside, boredom is “pervasive,” as children are often left “idle, sleeping or lying on the couches for long periods during the day.”

A 16-year-old boy and his father, immigrants from Honduras, wait for assistance with travel plans after being released from detention in Texas earlier this month. (Loren Elliott/AFP/Getty Images)

The study examined the experiences of 20 families who were detained in the Toronto and Laval holding centres and found that, in nearly half the cases, children ended up being separated from their parents at some point in the asylum-seeking process.

In detention, mothers are normally permitted to stay with their children. Fathers, on the other hand, are kept separate and only allowed to visit their spouse and children twice a day for about 15 to 30 minutes, according to the study.

In some cases, detained asylum seekers have lived in the country without status for years. In detention, they are given the option of keeping their Canadian-born children with them or sending them to live with extended family or in the custody of provincial youth protection services.

The minors detained last year spent an average of 13 days in custody, but the time period can vary significantly.

The study recounts how, in one instance, a six-year-old girl detained for more than six months asked her parents, “Are they gonna keep us here permanently?”

Feds aim to keep families together

Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale said earlier this week that children of immigrants and refugees are detained in Canada only as a last resort.

“Obviously, anyone looking at the human images [from the U.S.] would be very, very concerned,” Goodale said.

“Children are very precious creatures, and we all, I’m sure, need to have their safety, their security, their well-being first and foremost in our minds, and that is what lies at the very basis of Canadian policy.”

Last November, Goodale issued a directive to CBSA to keep children out of detention and keep families together “as much as humanly possible.”

The number of children in detention has dropped slightly under the Liberal government, though it’s on pace to rise again this year.

(Roberto Rocha/CBC)

Jenny Jeanes, a co-ordinator with the refugee advocacy group Action Réfugiés Montréal, said she still regularly sees children at the Laval detention centre she visits once a week.

“I’m not sure how well the directive is being applied in some cases,” she said.

Addressing reporters earlier this week, Goodale said new measures will soon be rolled out to offer alternatives to detention.

‘They have to show up’

Chantal Ianniciello, a Montreal immigration lawyer who represents clients in detention, said families would be better served by the regular process for asylum seekers, rather than being stuck in detention while they get the necessary documentation to identify themselves.

“The way I see it is that those people have an interest in going to court,” she said. “If they want to get status and get anything out of the system, they have to show up.”

Another study, produced last year by the International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto’s faculty of law, called on the government to find better alternatives to detention, including community housing.

Maru Mora leads a march outside a federal detention centre in Seattle, Wash., to protest the policy of separating children from their parents seeking asylum. (Alan Berner/The Seattle Times via Associated Press)

Denise Otis, a protection officer in the United Nations Refugee Agency, said she’s hopeful the Canadian government will work toward that goal.

“We imagine [the government] could find other ways to house them while they are trying to identify themselves.”

[ad_2]